Reforging Most Expensive Breastplate From Metropolitan Museum of Art

A 14th-century military martyr wears four layers, all patterned and richly trimmed: a cloak with tablion over a brusque dalmatic, another layer (?), and a tunic

Byzantine dress changed considerably over the thousand years of the Empire, but was substantially conservative. Popularly, Byzantine dress remained attached to its classical Greek roots with nearly changes and different styles beign evidenced in the upper strata of Byzantine society e'er with a touch of the Hellenic environment. The Byzantines liked colour and pattern, and made and exported very richly patterned cloth, especially Byzantine silk, woven and embroidered for the upper classes, and resist-dyed and printed for the lower. A different border or trimming round the edges was very common, and many single stripes down the torso or around the upper arm are seen, ofttimes denoting class or rank. Taste for the middle and upper classes followed the latest fashions at the Purple Court. As in the West during the Middle Ages, clothing was very expensive for the poor, who probably wore the same well-worn apparel about all the fourth dimension;[1] this meant in particular that any costume owned by well-nigh women needed to fit throughout the full length of a pregnancy.[2]

On the body [edit]

Mosaic from the San Vitale church in Ravenna. Few subsequently emperors would dress and then simply equally in a mosaic as Justinian I here, though his clothes is far richer at every point than his attendants. He and they have the tablion diagonally across their torsos. This bishop probably wore this manner of dress, which is very close to modern church vestments, for almost of the time. Note what appears to be shoes and socks.

In the early stages of the Byzantine Empire the traditional Roman toga was nevertheless used as very formal or official dress. By Justinian's time this had been replaced by the tunica, or long chiton, for both sexes, over which the upper classes wore other garments, similar a dalmatica (dalmatic), a heavier and shorter type of tunica, again worn by both sexes, just mainly by men. The hems often curve downwards to a sharp point. The scaramangion was a riding-coat of Persian origin, opening down the front and usually coming to the mid-thigh, although these are recorded as being worn by Emperors, when they seem to become much longer. In general, except for military machine and presumably riding-clothes, men of college status, and all women, had apparel that came downwardly to the ankles, or nearly then. Women often wore a top layer of the stola, for the rich in brocade. All of these, except the stola, might exist belted or not. The terms for dress are ofttimes disruptive, and certain identification of the proper noun a particular pictured item had, or the design that relates to a detail documentary reference, is rare, especially outside the Courtroom.

The chlamys, a semicircular cloak attached to the correct shoulder continued throughout the flow. The length roughshod sometimes simply to the hips or as far equally the ankles, much longer than the version normally worn in Ancient Greece; the longer version is too called a paludamentum. As well every bit his courtiers, Emperor Justinian wears ane, with a huge brooch, in the Ravenna mosaics. On each direct border men of the senatorial class had a tablion, a lozenge shaped coloured panel beyond the chest or midriff (at the front end), which was also used to evidence the farther rank of the wearer by the color or type of embroidery and jewels used (compare those of Justinian and his courtiers). Theodosius I and his co-emperors were shown in 388 with theirs at human knee level in the Missorium of Theodosius I of 387, but over the next decades the tablion tin be seen to motion higher on the Chlamys, for example in ivories of 413-414.[iii] A paragauda or border of thick fabric, normally including gilt, was also an indicator of rank. Sometimes an ellipsoidal cloak would be worn, especially by the war machine and ordinary people; it was not for court occasions. Cloaks were pinned on the right shoulder for ease of motion, and access to a sword.

Leggings and hose were ofttimes worn, but are not prominent in depictions of the wealthy; they were associated with barbarians, whether European or Farsi. Even basic wearing apparel appear to accept been surprisingly expensive for the poor.[ane] Some manual workers, probably slaves, are shown continuing to wear, at least in summer, the basic Roman slip costume which was effectively two rectangles sewn together at the shoulders and below the arm. Others, when engaged in activity, are shown with the sides of their tunic tied up to the waist for ease of movement.

Iconographic dress [edit]

Moses has iconographic dress, the others everyday contemporary wearing apparel, 10th century

The most common images surviving from the Byzantine catamenia are not relevant as references for bodily dress worn in the menstruation. Christ (oftentimes even as a infant), the Apostles, Saint Joseph, Saint John the Baptist and some others are almost always shown wearing formulaic dress of a big himation, a large rectangular mantle wrapped circular the body (almost a toga), over a chiton, or loose sleeved tunic, reaching to the ankles. Sandals are worn on the feet. This costume is not ordinarily seen in secular contexts, although possibly this is deliberate, to avoid confusing secular with divine subjects. The Theotokos (Virgin Mary) is shown wearing a maphorion, a more shaped pall with a hood and sometimes a hole at the neck. This probably is shut to actual typical wearing apparel for widows, and for married women when in public. The Virgin'south underdress may be visible, especially at the sleeves. In that location are also conventions for Sometime Attestation prophets and other Biblical figures. Apart from Christ and the Virgin, much iconographic apparel is white or relatively muted in colour particularly when on walls (murals and mosaics) and in manuscripts, just more brightly coloured in icons. Many other figures in Biblical scenes, especially if unnamed, are usually depicted wearing "contemporary" Byzantine clothing.

Female person wearing apparel [edit]

Modesty was important for all, and most women appear almost entirely covered past rather shapeless wearing apparel, which needed to be able to accommodate a full pregnancy. The basic garment in the early on Empire comes down to the ankles, with a high circular neckband and tight sleeves to the wrist. The fringes and cuffs might be busy with embroidery, with a ring around the upper arm also. In the 10th and 11th century a dress with flared sleeves, eventually very full indeed at the wrist, becomes increasingly popular, before disappearing; working women are shown with the sleeves tied up. In court ladies this may come with a V-collar. Belts were normally worn, perhaps with belt-hooks to support the skirt; they may accept been cloth more ofttimes than leather, and some tasselled sashes are seen.[four] Neck openings were probably often buttoned, which is hard to see in art, and not described in texts, merely must have been needed if merely for breast-feeding. Straight downwards, across, or diagonally are the possible options.[5] The plain linen undergarment was, until the 10th century, not designed to be visible. Withal at this signal a standing collar starts to show to a higher place the main dress.[5]

Hair is covered by a diverseness of head-cloths and veils, presumably oftentimes removed inside the home. Sometimes caps were worn nether the veil, and sometimes the cloth is tied in turban manner. This may take been done while working - for instance the midwives in scenes of the Nativity of Jesus in fine art commonly adopt this style. Earlier ones were wrapped in a figure-of-eight fashion, but by the 11th century circular wrapping, perchance sewn into a fixed position, was adopted. In the 11th and 12th centuries head-cloths or veils began to be longer.[vi]

With footwear, scholars are more than certain, as there are considerable numbers of examples recovered past archeology from the drier parts of the Empire. A cracking variety of footwear is found, with sandals, slippers and boots to the mid-calf all common in manuscript illustrations and excavated finds, where many are decorated in diverse ways. The color red, reserved for Majestic employ in male footwear, is actually by far the most common color for women'southward shoes. Purses are rarely visible, and seem to have been made of textile matching the wearing apparel, or perchance tucked into the sash.[7]

Dancers are shown with special clothes including short sleeves or sleeveless dresses, which may or may not have a lighter sleeve from an undergarment below. They have tight wide belts, and their skirts take a flared and differently coloured element, probably designed to rise up every bit they spin in dances.[viii] A remark of Anna Komnene about her mother suggests that not showing the arm above the wrist was a special focus of Byzantine modesty.[nine]

Although information technology is sometimes claimed that the face-veil was invented past the Byzantines,[10] Byzantine fine art does not depict women with veiled faces, although it usually depicts women with veiled hair. It is assumed that Byzantine women outside court circles went well wrapped up in public, and were relatively restricted in their movements exterior the house; they are rarely depicted in art.[11] The literary sources are non sufficiently clear to distinguish betwixt a head-veil and a face-veil.[9] Strabo, writing in the 1st century, alludes to some Farsi women veiling their faces (Geography, 11. 9-10).[ failed verification ] In addition, the early tertiary-century Christian author Tertullian, in his treatise The Veiling of Virgins, Ch. 17, describes pagan Arab women as veiling the entire confront except the eyes, in the style of a niqab. This shows that some Eye Eastern women veiled their faces long before Islam.

Colour [edit]

Ii embroidered roundels from an Egyptian 7th century tunic

Equally in Graeco-Roman times, purple was reserved for the royal family; other colours in various contexts conveyed data as to grade and clerical or government rank. Lower-class people wore simple tunics merely however had the preference for bright colours found in all Byzantine fashions.

The races in the Hippodrome used four teams: red, white, bluish and dark-green; and the supporters of these became political factions, taking sides on the great theological issues—which were also political questions—of Arianism, Nestorianism and Monophysitism, and therefore on the Imperial claimants who besides took sides. Huge riots took place, in the 4th to sixth centuries and mostly in Constantinople, with deaths running into the thousands, betwixt these factions, who naturally dressed in their appropriate colours. In medieval France, at that place were similar colours-wearing political factions, called chaperons.

Example [edit]

A 14th-century mosaic (right) from the Kahriye-Cami or Chora Church in Istanbul gives an excellent view of a range of costume from the late period. From the left, at that place is a soldier on baby-sit, the governor in one of the large hats worn by important officials, a middle-ranking civil retainer (holding the register roll) in a dalmatic with a wide border, probably embroidered, over a long tunic, which as well has a border. Then comes a higher-ranking soldier, conveying a sword on an untied chugalug or baldric. The Virgin and St Joseph are in their normal iconographic dress, and behind St Joseph a queue of respectable citizens wait their turn to register. Male person hem lengths driblet as the status of the person increases. All the exposed legs have hose, and the soldiers and citizens take foot-wrappings above, presumably with sandals. The citizens wear dalmatics with a wide border effectually the neck and hem, simply not as rich equally that of the middle-level official. The other men would perhaps article of clothing hats if not in the presence of the governor. A donor effigy in the aforementioned church, the Grand Logothete Theodore Metochites, who ran the legal system and finances of the Empire, wears an even larger lid, which he keeps on whilst kneeling earlier Christ (see Gallery).

Hats [edit]

Many men went bareheaded and, apart from the Emperor, they were commonly then in votive depictions, which may distort the tape we have. In the late Byzantine flow a number of extravagantly large hats were worn as uniform by officials. In the 12th century, Emperor Andronikos Komnenos wore a hat shaped like a pyramid, simply eccentric apparel is ane of many things he was criticised for. This was perhaps related to the very elegant lid with a very high-domed peak, and a sharply turned-upwardly brim coming far forwards in an astute triangle to a precipitous betoken (left), that was fatigued by Italian artists when the Emperor John VIII Palaiologos went to Florence and the Council of Ferrara in 1438 in the last days of the Empire. Versions of this and other wearing apparel, including many spectacular hats, worn by the visitors were carefully fatigued by Pisanello and other artists.[2] They passed through copies beyond Europe for use in Eastern subjects, especially for depictions of the three kings or Magi in Nascence scenes. In 1159 the visiting Crusader Prince Raynald of Châtillon wore a tiara shaped felt cap, embellished in gold. An Iberian wide brimmed felt hat came into vogue during the 12th century. Especially in the Balkans, minor caps with or without fur brims were worn, of the sort later adopted by the Russian Tsars.

Shoes [edit]

Not many shoes are seen conspicuously in Byzantine Art considering of the long robes of the rich. Carmine shoes marked the Emperor; blueish shoes, a sebastokrator; and green shoes a protovestiarios.

The Ravenna mosaics show the men wearing what may be sandals with white socks, and soldiers vesture sandals tied around the calf or strips of fabric wrapped round the leg to the calf. These probably went all the fashion to the toes (similar pes-wrappers are yet worn by Russian other ranks).

Some soldiers, including later Royal portraits in armed forces dress, show boots almost reaching the genu - red for the Emperor. In the Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Emperors there are shoes or slippers in Byzantine style fabricated in Palermo before 1220. They are short, only to the ankle, and generously cutting to allow many different sizes to be accommodated. They are lavishly decorated with pearls and jewels and gold scrollwork on the sides and over the toe of the shoe.[12] More than practical footwear was no doubt worn on less formal occasions.

Outside labourers would either have sandals or be barefoot. The sandals follow the Roman model of straps over a thick sole. Some examples of the Roman cuculus or military machine kick are also seen on shepherds.

Military costume [edit]

This stayed close to the Greco-Roman pattern, particularly for officers (see Gallery section for example). A breastplate of armour, under which the bottom of a short tunic appeared every bit a brim, oftentimes overlaid with a fringe of leather straps, the pteruges. Like strips covered the upper arms, below round armour shoulder-pieces. Boots came to the calf, or sandals were strapped high on the legs. A rather flimsy-looking textile belt is tied high under the ribs as a badge of rank rather than a applied particular.

Dress and equipment changed considerably beyond the period to have the most efficient and constructive accoutrements current economics would allow. Other ranks' wear was largely identical to that of common working men. The manuals recommend tunics and coats no longer than the knee.[13] Every bit an army marches first of all on its feet, the manual writers were more than concerned that troops should have good footwear than anything else.[fourteen] This ranged from depression lace up shoes to thigh boots, all to be fitted with "a few (hob) nails".[15] A head-cloth ("phakiolion" or "maphorion") which ranged from a simple cloth coming from below the helmet (as still worn by Orthodox clergy) to something more like a turban, was standard military headgear in the Eye and Late Empire for both common troops and for ceremonial wear past some ranks;[xvi] they were also worn past women.

Purple costume [edit]

The distinctive garments of the Emperors (often there were two at a time) and Empresses were the crown and the heavily jewelled Imperial loros or pallium, that adult from the trabea triumphalis, a ceremonial coloured version of the Roman toga worn by Consuls (during the reign of Justinian I Consulship became part of the imperial condition), and worn by the Emperor and Empress as a quasi-ecclesiastical garment. It was also worn past the twelve most important officials and the imperial babysitter, and hence by Archangels in icons, who were seen as divine bodyguards, its chief purpose was ideological, representing the different Hellenistic political values such equally the deification of the monarch and his role as the sole legislator and administrator of the democracy.[17] In practice it was only normally worn a few times a yr, such as on Easter Sunday, but it was very commonly used for depictions in art.[18]

The men's version of the loros was a long strip, dropping downwardly straight in front to below the waist, and with the portion backside pulled round to the front and hung gracefully over the left arm. The female loros was similar at the front stop, merely the dorsum end was wider and tucked under a belt after pulling through to the forepart again. Both male person and female versions changed style and diverged in the heart Byzantine period, the female later on reverting to the new male style. Apart from jewels and embroidery, small-scale enamelled plaques were sewn into the clothes; the dress of Manuel I Comnenus was described every bit beingness similar a meadow covered with flowers. Mostly sleeves were closely fitted to the arm and the outer clothes comes to the ankles (although oft called a scaramangion), and is as well rather closely fitted. The sleeves of empresses became extremely wide in the subsequently period.[19]

The imperial daily robe was a simpler and more idealized regalia of the diverse Hellenistic kings, depicted in various frescoes and miniatures, which featured the emperor in a simple "chiton" robe, a "chlamys" of various sizes, a regal diadem and the purple boots Tzangion of which elaborated examples are evidenced in imperial works such as the Paris psalter or the David plates, idealizing the concept of philanthropy and beneficence as the main roles of the perfect Hellenistic and Byzantine monarch.[xx]

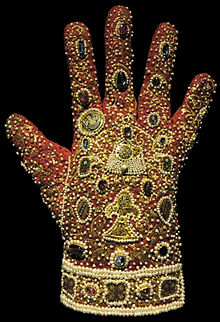

Glove from the Royal Regalia of the Holy Roman Emperors in Vienna, including enamelled plaques. Palermo, c. 1220

The superhumeral, worn throughout the history of Byzantium, was the imperial decorative collar, often forming part of the loros. Information technology was copied by at to the lowest degree women of the upper class. It was of cloth of golden or like material, then studded with gems and heavily embroidered. The decoration was by and large divided into compartments by vertical lines on the collar. The edges would be done in pearls of varying sizes in upwardly to iii rows. There were occasionally drop pearls placed at intervals to add to the richness. The collar came over the collarbone to embrace a portion of the upper chest.

The Regal Regalia of the Holy Roman Emperors, kept in the Schatzkammer (Vienna), contains a total set of outer garments fabricated in the twelfth century in substantially Byzantine style at the Byzantine-founded workshops in Palermo. These are among the best surviving Byzantine garments and requite a good thought of the lavishness of Purple formalism wear. There is a cloak (worn by the Emperors with the gap at the front end), "alb", dalmatic, stockings, slippers and gloves. The loros is Italian and later. Each chemical element of the design on the cloak (meet Textiles below) is outlined in pearls and embroidered in gold.

Peculiarly in the early on and later periods (approximately before 600 and subsequently 1,000) Emperors may be shown in war machine dress, with gilded breastplates, crimson boots, and a crown. Crowns had pendilia and became closed on top during the twelfth century.

Court dress [edit]

Court life "passed in a sort of ballet", with precise ceremonies prescribed for every occasion, to show that "Imperial power could be exercised in harmony and guild", and "the Empire could thus reflect the motility of the Universe equally it was made by the Creator", according to the Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, who wrote a Book of Ceremonies describing in enormous detail the annual round of the Court. Special forms of dress for many classes of people on particular occasions are set down; at the name-mean solar day dinner for the Emperor or Empress various groups of high officials performed ceremonial "dances", one group wearing "a blue and white garment, with short sleeves, and gilded bands, and rings on their ankles. In their hands they concur what are called phengia". The second grouping do just the aforementioned, but wearing "a garment of dark-green and red, split, with golden bands". These colours were the marks of the old chariot racing factions, the 4 at present merged to just the Dejection and the Greens, and incorporated into the official bureaucracy.

Various tactica, treatises on administrative structure, court protocol and precedence, give details of the costumes worn past unlike office-holders. According to pseudo-Kodinos, the distinctive colour of the Sebastokrator was blue; his ceremonial costume included blue shoes embroidered with eagles on a red field, a red tunic (chlamys), and a diadem (stephanos) in red and aureate.[21] Equally in the Versailles of Louis XIV, elaborate wearing apparel and courtroom ritual probably were at least partly an attempt to smother and distract from political tensions.

However this formalism way of life came under stress as the military crunch deepened, and never revived after the interlude of the Western Emperors following the capture of Constantinople by the 4th Crusade in 1204; in the late catamenia a French visitor was shocked to see the Empress riding in the street with fewer attendants and less anniversary than a Queen of France would accept had.

Clerical dress [edit]

This is certainly the expanse in which Byzantine and classic article of clothing is nearest to living on, as many forms of habit and vestments still in employ (specially in the Eastern, but also in the Western churches) are closely related to their predecessors. Over the menstruation clerical apparel went from beingness merely normal lay dress to a specialized set of garments for different purposes. The bishop in the Ravenna mosaic wears a chasuble very shut to what is regarded as the "modern" Western form of the 20th century, the garment having got much larger, and and so contracted, in the meantime. Over his shoulder he wears a simple bishop's omophorion, resembling the clerical pallium of the Latin Church, and a symbol of his position. This later became much larger, and produced various types of like garments, such as the epitrachelion and orarion, for other ranks of clergy. Modern Orthodox clerical hats are also survivals from the much larger and brightly coloured official headgear of the Byzantine civil service.

Hair [edit]

Men's pilus was by and large brusque and neat until the late Empire, and often is shown elegantly curled, probably artificially (film at peak). The 9th century Khludov Psalter has Iconophile illuminations which vilify the last Iconoclast Patriarch, John the Grammarian, caricaturing him with untidy pilus sticking straight out in all directions. Monk's hair was long, and nearly clergy had beards, equally did many lay men, especially later. Upper-grade women mostly wore their pilus up, over again very ofttimes curled and elaborately shaped. If nosotros are to judge past religious art, and the few depictions of other women outside the court, women probably kept their pilus covered in public, especially when married.

Textiles [edit]

Manuscript illumination of Emperor Nicephorus III Botaniates (1078-81) flanked past St John Chrysostomos and the Archangel Michael

Every bit in Mainland china, there were large Byzantine Imperial workshops, obviously always based in Constantinople, for textiles as for other arts like mosaic. Although at that place were other important centres, the Imperial workshops led manner and technical developments and their products were frequently used as diplomatic gifts to other rulers, also as being distributed to favoured Byzantines. In the belatedly tenth century, the Emperor sent golden and fabrics to a Russian ruler in the hope that this would prevent him attacking the Empire.

Nearly surviving examples were non used for clothes and feature very big woven or embroidered designs. Before the Byzantine Iconoclasm these often contained religious scenes such equally Annunciations, oft in a number of panels over a large piece of cloth. This naturally stopped during the periods of Iconoclasm and with the exception of church vestments [3] for the virtually part figural scenes did not reappear afterwards, beingness replaced by patterns and animal designs. Some examples testify very large designs being used for clothing by the great - two enormous embroidered lions killing camels occupy the whole of the Coronation cloak of Roger II in Vienna, produced in Palermo almost 1134 in the workshops the Byzantines had established there. [four] A sermon by Saint Asterius of Amasia, from the cease of the fifth century, gives details of imagery on the wearing apparel of the rich (which he strongly condemns):[22]

When, therefore, they dress themselves and appear in public, they look like pictured walls in the eyes of those that meet them. And perhaps fifty-fifty the children environs them, smile to ane some other and pointing out with the finger the moving-picture show on the garment; and walk along after them, following them for a long time. On these garments are lions and leopards; bears and bulls and dogs; woods and rocks and hunters; and all attempts to imitate nature by painting.... But such rich men and women as are more pious, accept gathered up the gospel history and turned it over to the weavers.... You lot may see the nuptials of Galilee, and the water-pots; the paralytic conveying his bed on his shoulders; the blind man being healed with the dirt; the woman with the encarmine issue, taking hold of the edge of the garment; the sinful adult female falling at the feet of Jesus; Lazarus returning to life from the grave....

Both Christian and pagan examples, mostly embroidered panels sewn into plainer fabric, accept been preserved in the exceptional conditions of graves in Arab republic of egypt, although more often than not iconic portrait-style images rather than the narrative scenes Asterius describes in his diocese of Amasya in northern Anatolia. The portrait of the Caesar Constantius Gallus in the Chronography of 354 shows several figurative panels on his clothes, more often than not round or oval (see gallery).

The silk shroud of Charlemagne manufactured in Constantinople c. 814

Early busy textile is mostly embroidered in wool on a linen base, and linen is generally more common than cotton throughout the period. Raw Silk yarn was initially imported from People's republic of china, and the timing and place of the first weaving of it in the Near Eastern world is a matter of controversy, with Arab republic of egypt, Persia, Syria and Constantinople all existence proposed, for dates in the 4th and 5th centuries. Certainly Byzantine textile ornamentation shows great Persian influence, and very footling direct from China. According to fable agents of Justinian I bribed two Buddhist monks from Khotan in about 552 to discover the undercover of cultivating silk, although much connected to be imported from Cathay.

Resist dyeing was mutual from the tardily Roman menstruum for those outside the Court, and woodblock printing dates to at to the lowest degree the 6th century, and possibly earlier - again this would part as a cheaper alternative to the woven and embroidered materials of the rich. Apart from Egyptian burial-cloths, rather fewer cheap fabrics have survived than expensive ones. It should too be remembered that depicting a patterned fabric in paint or mosaic is a very difficult task, oftentimes impossible in a small miniature, so the artistic record, which often shows patterned fabrics in large-calibration figures in the best quality works, probably nether-records the utilise of patterned material overall.

Gallery [edit]

-

Basil II in war machine dress, early on 11th century

Encounter also [edit]

- Ottoman clothing

- Sasanian dress

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Payne, Blanche; Winakor, Geitel; Farrell-Beck Jane: The History of Costume, from the Ancient Mesopotamia to the Twentieth Century, 2d Edn, p128, HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 0-06-047141-7

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006), p. 43

- ^ Kilerich, Bente, p. 275

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006), pp. 50-53;57

- ^ a b Dawson, Timothy (2006), pp. 53-54

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006), pp. 43-47

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006), pp. 57-59

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006), pp. 59-sixty

- ^ a b Dawson, Timothy (2006), p. 61

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006) 61, gives two examples; Review of Herrin book

- ^ Michael Angold, Church and Lodge in Byzantium Nether the Comneni, 1081-1261, pp. 426-7 & ff;1995, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-26986-5

- ^ Photo that does not show the gold embroidery very well. [i] As well run across Eatables images of the Regalia.

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2007), p. 16

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2007), p. 18

- ^ Strategikon. Leo, Taktika

- ^ Dawson, Timothy (2006), pp. 44-45; Phokas, Composition on Warfare, on mutual troops, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, Treatise on Royal Military Expeditions

- ^ Alexander, Suzanne Spain (1977). Heraclius, byzantine majestic ideology, and the David plates. OCLC 888246271.

- ^ Parani, Maria Thousand. pp 18-27

- ^ Parani, Maria G. pp xix-27

- ^ Alexander, Suzanne Spain (1977). Heraclius, byzantine imperial ideology, and the David plates. OCLC 888246271.

- ^ Parani, Maria G. (2003). Reconstructing the reality of images: Byzantine textile culture and religious. iconography (11th to 15th centuries) . BRILL. pp. 63, 67–69, 72. ISBN978-90-04-12462-2.

- ^ Asterius of Amasia Online English translation - near the beginning

References [edit]

- Robin Cormack, "Writing in Aureate, Byzantine Social club and its Icons", 1985, George Philip, London, ISBN 0-540-01085-5

- Dawson, Timothy. Women'due south Clothes in Byzantium, in Garland, Lynda (ed), Byzantine women: varieties of experience 800-1200, 2006, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-5737-10, 9780754657378.

- Dawson, Timothy (2007). Byzantine infantryman: Eastern Roman empire c.900-1204. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN978-1846031052.

- Kilerich, Bente, "Representing an Emperor: Way and Significant on the Missorium of Theodosius I", in Almagro-Gorbea, Álvarez Martínez, Blázquez Martínez y Rovira (eds.), El Disco de Teodosio, 2000, Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid, ISBN 84-89512-60-iv

- Parani, Maria Thou. (2003). Reconstructing the Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography (11th–15th Centuries. Leiden: Brill. ISBN9004124624.

- Steven Runciman, Byzantine Manner and Culture, 1975, Penguin

- David Talbot-Rice, Byzantine Art, tertiary edn 1968, Penguin Books Ltd

- L Syson & Dillian Gordon, "Pisanello, Painter to the Renaissance Courtroom",2001, National Gallery Company, London, ISBN 1-85709-946-X

Farther reading [edit]

- Ball, Jennifer 50., Byzantine Dress: Representations of Secular Dress, 2006, Macmillan, ISBN 1403967008

- Costello, Angela L., "Material Wealth and Immaterial Grief: The Terminal Volition and Attestation of Kale Pakouriane.", 2016. Academia.edu

External links [edit]

- A newer await at Byzantine Vesture.

- Photos of major pieces of extant medieval clothing, some Byzantine (including some of the Imperial Regalia) by Cynthia du Pré Silver

- Exhibition online characteristic from the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, NY Byzantium, Faith and Power, 1261-1453 - Gallery V in detail; Byzantium: faith and ability (1261-1557), an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online equally PDF)

- Byzantine fashion

- Some plates from a German 19th-century history of costume

- A weblog on Byzantine clothing for historical reenactors.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_dress

0 Response to "Reforging Most Expensive Breastplate From Metropolitan Museum of Art"

Postar um comentário